Ciceronian Justice in

Lactantius’ and Augustine’s

Political Thought

This subproject tackles the foundation of much of what the West knew of Cicero’s conception of justice throughout the history of political thought, until the discovery in 1819 of the palimpsest of parts of the Republic in the Vatican library. Cicero’s conception of justice came to be known to medieval and early modern Europe through Lactantius’ and Augustine’s discussion and fragmented transmission of the Carneadean debate in their own works. It was on the basis of the normative framework Lactantius and especially Augustine had established for thinking about Roman justice, virtue and imperialism that the Roman conceptions of justice contained in the debate became influential and reached a wide audience. The church fathers’ ultimately dismissive approach to the “pagan virtues” framed arguments about Ciceronian political ideas and Roman justice far into early modern thought; their influence is especially marked in Machiavelli and Gentili (for the reception of Augustine, see now Pollmann and Otten 2013).

A Missing Link

The subproject seeks to provide one crucial “missing link” between Cicero’s theory of justice and early modern attempts at reviving Roman ideas—a treatment of Lactantius’ and Augustine’s respective discussions of the Carneadean debate (Maier 1955; Testard 1958; Hand 1970; Deproost 1979; Girardet 1995; Fortin 1997; Horn 1999; Stock 1996; Horn 1999).

Lactantius and Augustine, mostly due to very different political contexts, diverge starkly in their political theories (Garnsey 2002), but Augustine’s treatment of the Carneadean debate in City of God owes much to Lactantius’ Divine Institutes (Bowen and Garnsey 2004: 29-35). Augustine’s account, more ambiguous toward Roman conceptions of justice than Lactantius’ very critical approach, was instrumental in leaving posterity a distorted yet influential view of glory-seeking as the chief “pagan virtue” (Christes 1980; Warner and Scott 2011; Irwin 2007). The literature on Augustine’s political thought is immense (starting points are Deane 1963; Baynes 1968; Markus 1989; Horn 1997; Weithman 2001; O’Daly 2004); for Lactantius, the bibliography in Bowen and Garnsey’s translation of the Institutes provides an entry point (Bowen and Garnsey 2004: 443-452; and see on the historical background Digeser 2006).

This subproject will examine the way Lactantius and Augustine used the Carneadean debate to criticize Ciceronian ideas of justice, with a view both backwards to the classical origin and forward to the later uses of the debate. Augustine’s ambiguous account of the justice of Roman empire proved a difficult obstacle both for anti-imperialist writers (such as de Soto) and for natural lawyers later on—which raises the question, to what extent did this ambiguity result from his reception of the Carneadean debate?

The Christian apologist L. Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius’ (c. 250-c. 325) treatment of the Carneadean debate showed little sympathy for Cicero’s theory of natural law. He is inclined to present Carneades’ skeptical stance and his anti-Ciceronian arguments as effective, both because he thinks that Cicero as a pagan could not possibly have refuted Carneades’ skepticism, and because Lactantius is hostile to the Roman empire of his own day (Bowen and Garnsey 2004). It remained for Augustine to explain how the Romans could have been given their empire by God in the first place (Maier 1955; Deane 1963; Baynes 1968; Markus 1989; Weithman 2001; O’Daly 2004).

Christian vs. Pagan Justice

Augustine, more sympathetic to Cicero’s defense against Carneades’ skeptical argument than Lactantius, integrates the debate into a historical view that accords the Romans some virtues due to which they have gained their empire—adherence to law is mentioned, but above all what Augustine thinks of as the pagan virtue par excellence, glory (gloria or amor laudis). Augustine’s account was as influential as it is ambiguous; given the pagan nature of the Roman empire the Romans could never achieve true justice (De civ. D. 19.21; cf. Klaus Martin Girardet 1995; Fortin 1997). What role did the Carneadean debate play in Augustine’s strong emphasis on the gulf separating Christian vera iustitia from Roman justice? And what was the weight assigned by Augustine and Lactantius to their classical sources? Had Laelius’ (or rather Cicero’s) defense of justice lost its force entirely for Augustine?

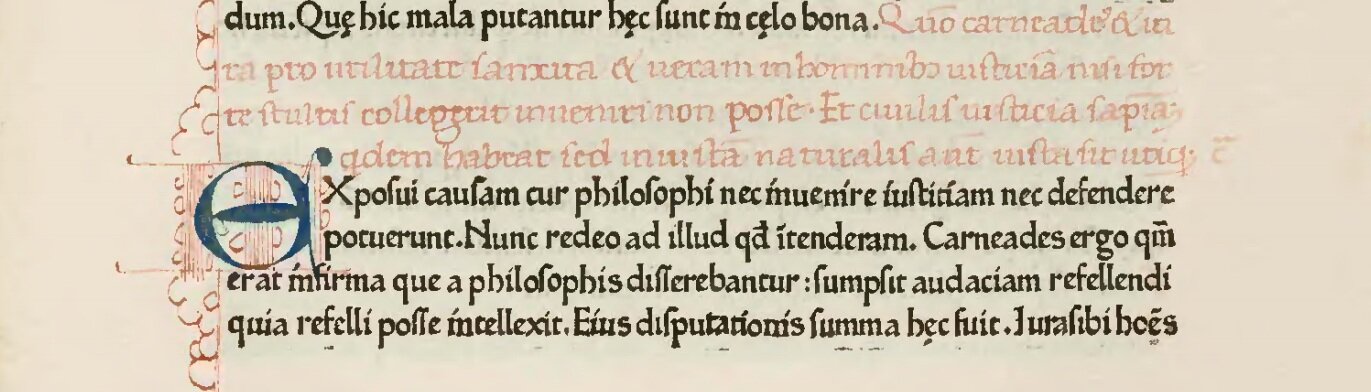

Cicero’s treatment of justice in book 3 of the Republic had introduced an international element and, most importantly, imperialism into the discussion. Once we get to the Carneadean debate as it appears in the church fathers, we encounter additional layers added to it. Lactantius in his Divine Institutes, a work he was provoked into writing by emperor Diocletian’s Great Persecution which began in 303, quotes the central argument that is being put forward in the Republic against Carneades’ skeptical, anti-imperialist stance verbatim—Cicero’s Stoic (for the Stoics as Carneades’ main target, see Cic. Tusc. 5.83) description of the natural law that serves as an objective yardstick for justice and according to which the Roman empire had been gained justly (Cic. Rep. 3.33=Lact. Inst. 6.8.7-9). But Lactantius only cites the passage from Republic 3 in order to then show that justice, properly understood, had in fact been absent from Rome. He is inclined to present Carneades’ anti-Ciceronian arguments as effective as far as they go, both because he thinks that Cicero as a pagan could not possibly have refuted Carneades’ skepticism, and because Lactantius is of course rather hostile to the Roman empire of his own day.

Lactantius goes on to say that (Inst. 6.8.11f., trans. Bowen/Garnsey) “if Cicero had also known or explained what instructions the holy law itself consists in as clearly as he saw its force and reason, he would have fulfilled the role not of a philosopher but of a prophet. That, however, he could not do, and so we must.” Of Carneades’ anti-imperialist argument Lactantius wrote that Carneades did actually “overthrow” “all that was being said in its [justice’s] favour.” This was easily possible according to Lactantius because (Inst. 5.14.5f.) pagan justice “had no roots; at the time there was no justice on earth, so that its nature and quality could not be identified by philosophers,” something that for Lactantius had of course changed with the arrival of Christianity. Lactantius’ own argument against Carneades relied on the idea of a divine reward for virtue, which implied an anti-Stoic view of virtue as not being an end in itself (Lact. Inst. 5.14.5f.).

Glory, a Virtue for the Earthly City…

Lactantius tilted the Carneadean debate dangerously in favor of Carneades’ skeptical, Epicurean stance (at least in the absence of Christianity). Augustine, somewhat more sympathetic to Cicero’s defense against Carneades’ skeptical argument, does not himself really try to refute Carneades’ case against justice (on Augustine’s knowledge of Cicero, see (Testard 1958; Stock 1996). When he discusses (De civ. D. 5.12, trans. W. M. Green) “By what virtues the ancient Romans gained the favour of the true God, so that he increased their empire although they did not worship him,” Augustine quotes Sallust (Cat. 7.6) and answers that the Romans had been “eager for praise” and “sought unbounded glory.”

Augustine goes on to say, thereby creating a highly influential legacy the impact of which is obvious in Machiavelli (Warner and Scott 2011), that (De civ. D. 5.12) “this glory they [the Romans] most ardently loved. For its sake they chose to live and for its sake they did not hesitate to die. They suppressed all other desires in their boundless desire for this one thing.” But glory and the love of praise are virtues only in a very tenuous sense: Augustine does call glory-seeking a virtue of sorts, but then almost immediately hedges his bets, quoting Sallust (Cat. 11.1-2) to the effect that ambition and glory-seeking, as opposed to avarice, was in fact “a vice,” albeit one “that comes close to being a virtue.”

… or Just a Splendid Vice?

At times Augustine makes it clear, unambiguously, that glory is but a name the Romans used to hide crimes motivated by their lust for domination (De civ. D. 3.14: libido dominandi). Importantly, Augustine imputes to Cicero this exact notion of glory as the chief pagan virtue. He argues that “men who do not obtain the gift of the Holy Spirit and bridle their baser passions by pious faith and by love of intelligible beauty, at any rate live better because of their desire for human praise and glory,” and goes on to claim that “Cicero also could not disguise this fact. “[N]ot even in his philosophical works,” Augustine writes, “did Cicero shrink from this pestilential notion, for he declares allegiance to it in them as plain as day.” By “philosophical works” the church father here means Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, in fact a highly rhetorical work, where Cicero makes a throwaway remark on the motivational power of glory which Augustine fastens upon (De civ. D. 5.13, citing Cic. Tusc. 1.4; for a more representative take on Cicero’s view of glory in that work, however, cf. Tusc. 5.102). Ultimately, glory-seeking remains a vice, or a pagan virtue at best; men “like Scaevola, Curtius and the Decii” were merely “citizens of the earthly city,” who, in the absence of eternal life, could not be motivated but by glory (De civ. D. 5.14).